log4net Tutorial - The Complete Guide for beginners and pros

log4net is still one of the most commonly used logging frameworks for .NET. While originally being a port of the log4j logging framework for Java, a lot has happened over the years, to make log4net a unique logging option for .NET/C# developers. This post is a collection of descriptions, examples, and best practices I would have liked to have had when starting with log4net 10 years ago.

To make sure everyone follows, let me start by explaining what log4net is. Whether you are just getting started or have years of experience writing software, you probably know the concept of logging. Small pieces of text, written to the console, a file, a database, you name it, which will track what your software is doing and help you debug errors after they happen. log4net is one of three very popular frameworks for implementing log messages in your application (Serilog and NLog being the other two). log4net works with almost any version of .NET (including .NET Core).

I don't recommend log4net for new projects. Check out NLog vs log4net and Serilog vs log4net for more details.

Logging

I guess you are here to learn about logging messages with log4net, so I'll start by showing you how to do just that. To understand log4net, you will need some basic knowledge about a concept in log4net called Levels.

Log levels

All log messages written through log4net must be assigned one of the five following levels:

- Debug

- Info

- Warn

- Error

- Fatal

By assigning a log level to each message, you will be able to filter on level, notify on specific levels, etc. More about this later in this tutorial.

Logging messages

Now that you understand log levels, let's write some log messages. Messages are logged using a log4net class named ILog. To get an instance of the ILog class, use the LogManager as illustrated here:

ILog log = LogManager.GetLogger("mylog")

In the example, I retrieved an instance of ILog by calling the GetLogger-method with the name of the logger. I won't go into details about named loggers just yet, so don't worry too much about the mylog-parameter.

With our new logger, logging messages through log4net is easy using one of the provided methods:

log.Info("This is my first log message");

Notice the name of the method being Info. This tells log4net that the log message specified in the parameter is an information message (remember the log levels?). There are log methods available for all 5 log levels:

log.Debug("This is a debug message");

log.Info("This is an information message");

log.Warn("This is a warning message");

log.Error("This is an error message");

log.Fatal("This is a fatal message");

Log messages can be constructed dynamically by either using string interpolation or by using the provided *Format-methods available on ILog:

var name = "Thomas";

log.Info($"Hello from {name}");

log.InfoFormat("Hello from {0}", name); // Same result as above

Both lines result in the line Hello from Thomas being logged.

Logging is often used to log that errors are happening, why you may have an Exception object you want to log. Rather than calling ToString manually, there are overloads accepting exceptions too:

try

{

// Something dangerous!

}

catch (Exception e)

{

log.Error("An error happened", e);

}

Logging the exception using this approach, will open up a range of possibilities which I will show you later in this tutorial.

If you want full control of the log message being logged, you can use the Log-method on the Logger property:

log.Logger.Log(new LoggingEvent(new LoggingEventData

{

Level = Level.Error,

Message = "An error happened"

}));

You normally don't need to use this method, since message details can be set using other and better (IMO) features provided by log4net.

Contexts

You might want to include repeating properties or pieces of information on all log messages. An example of this could be an application name if multiple applications are logging into the same destination. log4net provides several context objects for you to define contextual information like this.

In the example of adding an application name to all messages logged through log4net, use the GlobalContext class:

GlobalContext.Properties["Application"] = "My application";

By setting the Application property like this, My application will automatically be written as part of each log message (if configured correctly).

Like global properties, you can set up custom properties visible from the current thread only using the ThreadContext class:

ThreadContext.Properties["ThreadId"] = Thread.CurrentThread.ManagedThreadId;

In the example, I stored the current thread id in the variable ThreadId. Storing thread IDs like this can help you debug a problem later on.

In the case where you want to attach a custom property to one or more log message of your choice, but don't want the property value as part of the text message, you can utilize the using construct in C#:

using (ThreadContext.Stacks["url"].Push("http://localhost/about"))

{

log.Info("This is an information message");

...

log.Debug("This is a debug message");

}

log.Info("This won't get url");

In the example, I pushed a variable named url to all log messages written inside the using. In the example, the url property is included in both log messages inside the using but not the log message outside.

Configuration

Up until this point, I didn't add a single line of configuration. I told log4net which messages to log, but never where and how to log them. Let's change that! Like logging messages, there are some key features you will need to understand to configure log4net. Let's dig in.

Appenders

Appenders are the most important feature to understand when dealing with log4net configuration. If you understand appenders, you can read and understand most log4net configuration files out there.

So what is an appender? For log4net to know where to store your log messages, you add one or more appenders to your configuration. An appender is a C# class that can transform a log message, including its properties, and persist it somewhere. Examples of appenders are the console, a file, a database, an API call, elmah.io, etc. There are appenders for pretty much every database technology out there. Check out a search for log4net.appender on nuget.org to see some of them: https://www.nuget.org/packages?q=log4net.appender.

Look ma, I'm configured in XML

log4net is typically configured using XML in either the web/app.config file or in a separate log4net.config file. Later, I'll show you how to configure it in code, but that isn't common practice. The simplest possible configuration, writes all log messages to the console. It's a great starting point for checking that logging configuration is correctly picked up by log4net:

<log4net>

<appender name="ConsoleAppender" type="log4net.Appender.ConsoleAppender">

<layout type="log4net.Layout.PatternLayout">

</layout>

</appender>

<root>

<level value="ALL" />

<appender-ref ref="ConsoleAppender" />

</root>

</log4net>

Let's go through each element. All of the configuration is wrapped inside the log4net element. This element will be the root element when using a log4net.config file and nested beneath the configuration element when included in an app/web.config file. I'll be using an app.config file for this example, that looks similar to this:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8" ?>

<configuration>

<configSections>

<section name="log4net" type="log4net.Config.Log4NetConfigurationSectionHandler, log4net" />

</configSections>

<log4net>

<appender name="ConsoleAppender" type="log4net.Appender.ConsoleAppender">

<layout type="log4net.Layout.PatternLayout">

</layout>

</appender>

<root>

<level value="ALL" />

<appender-ref ref="ConsoleAppender" />

</root>

</log4net>

</configuration>

To get IntelliSense on log4net config, download this XML schema: http://csharptest.net/downloads/schema/log4net.xsd. Open your config file and click XML | Schemas... inside Visual Studio. Add the downloaded XML schema and IntelliSense is provided. There are some other schemas floating around on GitHub too, but these don't seem to be working inside app/web.config files.

That was quite a detour. Inside the log4net element, there are two key elements: appender and root. You can add as many appender elements as you'd like. As we learned in the previous section, appenders are used to tell log4net about where to store log messages. In the example, I'm using the log4net.Appender.ConsoleAppender which (surprise!) shows log messages on the console. The layout element inside appender is used to tell log4net how to format each log message. I'm not specifying any format here, why log4net simply outputs the log message.

In the root element, I tell log4net to log the log level ALL to ConsoleAppender. ALL is a shortcut for all 5 log levels.

To show you a couple of example outputs, I'll re-use the following C# code:

log.Debug("This is a debug message");

log.Info("This is an information message");

log.Warn("This is a warning message");

log.Error("This is an error message");

log.Fatal("This is a fatal message");

When running the program with these lines and the default XML configuration above, the output is the following:

This is a debug message

This is an information message

This is a warning message

This is an error message

This is a fatal message

To spice things up, let's define a better layout in the config file:

<appender name="ConsoleAppender" type="log4net.Appender.ConsoleAppender">

<layout type="log4net.Layout.PatternLayout">

<conversionPattern value="%date %level %message%newline" />

</layout>

</appender>

Including the %date and %level variables make the log output more informative:

2019-05-02 14:03:30,556 DEBUG This is a debug message

2019-05-02 14:03:30,565 INFO This is an information message

2019-05-02 14:03:30,565 WARN This is a warning message

2019-05-02 14:03:30,566 ERROR This is an error message

2019-05-02 14:03:30,566 FATAL This is a fatal message

Threshold

In the previous examples, we only added a single appender to the configuration. In most cases, you want to log messages to multiple appenders like both the console and a cloud service. In this case, the minimum log level will be different depending on which appender we want to log to. log4net provides a configuration option named threshold that can be used to do just that. Let's take a look at a quick example:

<log4net>

<appender name="ConsoleAppender" type="log4net.Appender.ConsoleAppender">

<!-- ... -->

</appender>

<appender name="FileAppender" type="log4net.Appender.FileAppender">

<!-- ... -->

</appender>

<root>

<level value="DEBUG" />

<appender-ref ref="ConsoleAppender" />

<appender-ref ref="FileAppender" />

</root>

</log4net>

In this example, we define two appenders and log the severity DEBUG and up to both appenders. This is defined in the level element. DEBUG is globally for all appenders added to the root element. As an example, we'll change file logging to only log WARNING and up by adding the threshold element to the FileAppender element:

<log4net>

<appender name="ConsoleAppender" type="log4net.Appender.ConsoleAppender">

<!-- ... -->

</appender>

<appender name="FileAppender" type="log4net.Appender.FileAppender">

<!-- ... -->

<threshold value="WARNING" />

</appender>

<root>

<level value="DEBUG" />

<appender-ref ref="ConsoleAppender" />

<appender-ref ref="FileAppender" />

</root>

</log4net>

When added directly to the appender, this is specific to that appender. The ConsoleAppender will keep using the DEBUG severity added to root.

Configuration in appSettings

While the log4net element contains everything you need to configure elmah.io, it is sometimes preferred to specify some settings as appSettings. Doing so will make it a lot easier to replace on deploy time using Octopus Deploy, Azure DevOps, config transformations, and similar. Overwriting appSettings on Azure is also a lot easier than trying to replace elements buried deep within the log4net element.

log4net provides a feature named pattern strings to address this. Let's look at a quick example to see how patterns can be applied to the configuration file:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8" ?>

<configuration>

...

<appSettings>

<add key="layout" value="%date %level %message%newline"/>

</appSettings>

<log4net>

<appender name="ConsoleAppender" type="log4net.Appender.ConsoleAppender">

<layout type="log4net.Layout.PatternLayout">

<conversionPattern type="log4net.Util.PatternString" value="%appSetting{layout}" />

</layout>

</appender>

<root>

<level value="ALL" />

<appender-ref ref="ConsoleAppender" />

</root>

</log4net>

</configuration>

In the example, I've moved the value of the conversionPattern from the previous example to a new appSettings value named layout. To reference the layout setting, add type="log4net.Util.PatternString" to the element you want to replace values (in this case the conversionPattern element) and reference the setting using its name: value="%appSetting{layout}".

Having the option to mix and match the configuration in both the log4net and appSettings elements quickly get addictive.

Commonly used appenders

Logging to the console is great when developing locally. Once your code hits a server, you always want to store your log messages in some kind of persistent storage. This can be everything from a simple file directly on the file system, over database products like SQL Server and Elasticsearch, to clouding logging platforms like elmah.io.

Console and file

Let's start simple. In the following example, I'm sending all log messages to both the console and a file:

<log4net>

<appender name="ConsoleAppender" type="log4net.Appender.ConsoleAppender">

<layout type="log4net.Layout.PatternLayout">

<conversionPattern value="%date %level %message%newline" />

</layout>

</appender>

<appender name="FileAppender" type="log4net.Appender.FileAppender">

<file value="log-file.txt" />

<appendToFile value="true" />

<layout type="log4net.Layout.PatternLayout">

<conversionPattern value="%date %level %message%newline" />

</layout>

</appender>

<root>

<level value="ALL" />

<appender-ref ref="ConsoleAppender" />

<appender-ref ref="FileAppender" />

</root>

</log4net>

The ConsoleAppender part matches the one from the previous example. I've added a new appender element, which references the log4net.Appender.FileAppender in the type attribute. As you probably already guessed, this appender writes log messages to a file. The appender is configured using sub-elements, like the file element to tell the appender which file to log to. Finally, notice that both appender names are referenced in the root element.

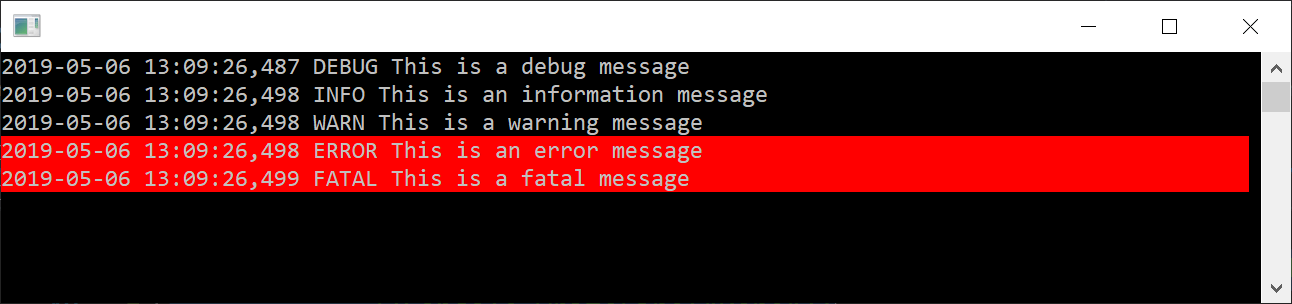

ColoredConsole and RollingFile

Logging to the console and a file is the simplest appenders included in log4net. While they work great for a tutorial like this, I would recommend you to use two alternatives:

<log4net>

<appender name="ColoredConsoleAppender" type="log4net.Appender.ColoredConsoleAppender">

<mapping>

<level value="ERROR" />

<foreColor value="White" />

<backColor value="Red, HighIntensity" />

</mapping>

<layout type="log4net.Layout.PatternLayout">

<conversionPattern value="%date %level %message%newline" />

</layout>

</appender>

<appender name="RollingFileAppender" type="log4net.Appender.RollingFileAppender">

<file value="logfile" />

<appendToFile value="true" />

<rollingStyle value="Date" />

<datePattern value="yyyyMMdd-HHmm" />

<layout type="log4net.Layout.PatternLayout">

<conversionPattern value="%date %level %message%newline" />

</layout>

</appender>

<root>

<level value="ALL" />

<appender-ref ref="ColoredConsoleAppender" />

<appender-ref ref="RollingFileAppender" />

</root>

</log4net>

ColoredConsoleAppender is basically ConsoleAppender on steroids. Using the mapping element, you can control the colors of the log messages in the console. In the example above, errors are marked with a red background color:

A simple thing as to be able to quickly spot errors happening in a 500 line log output can be a game-changer.

Likewise, RollingFileAppender is a specialization of FileAppender which does rolling logs. If you are not familiar with the term rolling log, let me spend a few words elaborating on that. Applications typically log A LOT of data. If you keep logging messages to the same file, your file will quickly grow to GBs or even TBs in size. Files aren't an optimal solution to store data that you want to be able to search in, but searching in large files is pretty much impossible. Using rolling files, you tell log4net to split up your files in chunks. Rolling logging can be configured by size, dates, and more. You often see people configuring a log file per day.

elmah.io

You can log to elmah.io through log4net too. To do so, install the elmah.io.log4net NuGet package:

Install-Package elmah.io.log4net

Configure the elmah.io log4net appender in your config file:

<log4net>

<appender name="ElmahIoAppender" type="elmah.io.log4net.ElmahIoAppender, elmah.io.log4net">

<logId value="LOG_ID" />

<apiKey value="API_KEY" />

</appender>

<root>

<level value="WARN" />

<appender-ref ref="ElmahIoAppender" />

</root>

</log4net>

Remember to replace LOG_ID and API_KEY with the correct values from elmah.io. That's it! All warn, error, and fatal messages are logged to elmah.io.

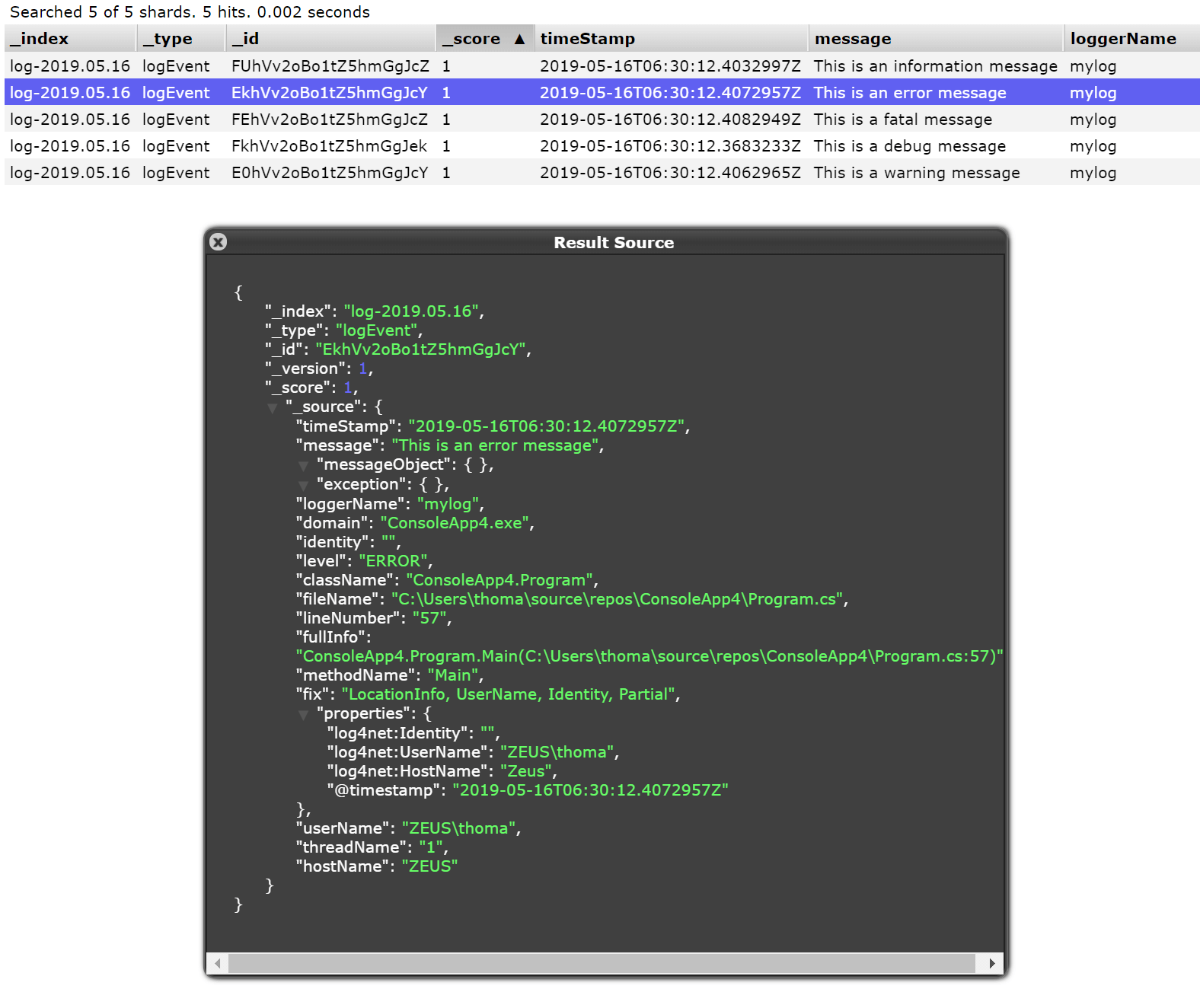

Elasticsearch

If you want to self-host everything and need to create custom dashboards over your log data, Elasticsearch is a great option. We've used Elasticsearch since founding elmah.io back in 2013 and are very satisfied with that choice.

log4net supports Elasticsearch through a couple of appenders available on NuGet. The best one (IMO) is log4net.ElasticSearch by JP Toto. To get started, install the NuGet package:

Install-Package log4net.ElasticSearch

Then add configuration to your web/app.config or log4net.config:

<log4net>

<appender name="ElasticSearchAppender" type="log4net.ElasticSearch.ElasticSearchAppender, log4net.ElasticSearch">

<connectionString value="Scheme=http;Server=localhost;Index=log;Port=9200;rolling=true"/>

<bufferSize value="1" />

</appender>

<root>

<level value="ALL" />

<appender-ref ref="ElasticSearchAppender" />

</root>

</log4net>

There are a lot of configuration options available with the package, why I encourage you to check out the documentation. For this example, I've included a minimal set of options. The connectionString element contains the information needed for the appender to communicate with Elasticsearch. I've included rolling=true creating a new index per day. This is especially handy when needing to clean up old log messages. Finally, I've set bufferSize to 1 to ensure that every log statement is stored in Elasticsearch without any delay. It is not recommended to do this in production, though. Analyze your need and set the value to something between 10-100.

When running my demo application, log messages are now successfully persisted in Elasticsearch:

Configuration in C#

I promised you an example of log4net configuration in C#. You won't find a lot of documentation or blog posts utilizing this approach, but it is possible. Let's configure the example from previously in C#:

var hierarchy = (Hierarchy)LogManager.GetRepository();

PatternLayout patternLayout = new PatternLayout

{

ConversionPattern = "%date %level %message%newline"

};

patternLayout.ActivateOptions();

var coloredConsoleAppender = new ColoredConsoleAppender();

coloredConsoleAppender.AddMapping(new ColoredConsoleAppender.LevelColors

{

BackColor = ColoredConsoleAppender.Colors.Red,

ForeColor = ColoredConsoleAppender.Colors.White,

Level = Level.Error

});

coloredConsoleAppender.Layout = patternLayout;

var rollingFileAppender = new RollingFileAppender

{

File = "logfile",

AppendToFile = true,

RollingStyle = RollingFileAppender.RollingMode.Date,

DatePattern = "yyyyMMdd-HHmm",

Layout = patternLayout

};

hierarchy.Root.AddAppender(coloredConsoleAppender);

hierarchy.Root.AddAppender(rollingFileAppender);

hierarchy.Root.Level = Level.All;

hierarchy.Configured = true;

BasicConfigurator.Configure(hierarchy);

I won't go into details on each line. If you look through the previous example in XML and this C#-based example, you should be able to see the mapping. The important part here is to call BasicConfigurator.Configure(hierarchy) instead of XML configuration in AssemblyInfo.cs.

Troubleshooting problems

Problems setting up logging is quite normal so don't feel bad if you ended up here because something doesn't work as expected. A logger configuration not actually logging messages to the configured appended(s) can be very hard to debug without some help. Luckily, log4net provides an internal logger that will help you debug all sorts of problems by being transparent about both the inner workings of log4net as well as any internal exceptions happening while configuring a logger or during logging.

To enable log4net's internal debug logger, include the following in your app.config/web.config file:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?>

<configuration>

<appSettings>

<add key="log4net.Internal.Debug" value="true"/>

</appSettings>

<!-- ... -->

</configuration>

This will output a lot of details from the "engine room" and make debugging wrong config and similar problems much easier. As a default, the log output will be written to the console. You may not always have access to the console if logging from web apps, Windows applications, services, or similar. To output the log messages to a file, extend the config file with the following markup:

<system.diagnostics>

<trace autoflush="true">

<listeners>

<add

name="textWriterTraceListener"

type="System.Diagnostics.TextWriterTraceListener"

initializeData="C:\temp\log4net-internal.log" />

</listeners>

</trace>

</system.diagnostics>

Dependency injection

Until now, we have created a new instance of the ILog implementation by calling the GetLogger method on the LogManager class. While I normally swear to dependency injection, I believe this is a nice and simple way to do logging: Declare a static ILog variable at the top of the class and we're done. Some prefer injecting the ILog class instead, which is perfectly valid with log4net too.

How you implement dependency injection of the logger is up to the IoC container you are using. For ASP.NET Core and the feature set available in the Microsoft.Extensions.DependencyInjection.Abstractions package, you can implement code similar to this:

services.AddScoped(factory => LogManager.GetLogger(GetType()));

This will add a scoped instance of ILog available for injection:

public class HomeController : Controller

{

private readonly ILog log;

public HomeController(ILog log)

{

this.log = log;

}

}

The code above serves as illustrations only. If logging with log4net from ASP.NET Core, I would recommend you to log through Microsoft.Extensions.Logging like illustrated in this sample.

.NET Core

I sometimes read people stating that log4net doesn't work with .NET Core/.NET 5 and forward. While I would recommend you to look at some of the other logging frameworks already mentioned, log4net works perfectly with .NET Core. To use log4net from .NET core, you need to install at least version 2.0.7 since they started targeting .NET Standard from that version and forward.

ASP.NET Core

log4net works with ASP.NET Core and the ILogger interface as well. To set this up in your application start by installing the Microsoft.Extensions.Logging.Log4Net.AspNetCore NuGet package:

dotnet add package Microsoft.Extensions.Logging.Log4Net.AspNetCore

Next, add your log4net configuration through the log4net config file. There is nothing specific to ASP.NET Core required for the configuration, as long as you make sure that any configured appenders are targeting netstandard or .NET Core.

Finally, add log4net in the ConfigreLogging method in the Program.cs file:

public class Program

{

public static void Main(string[] args)

{

CreateWebHostBuilder(args).Build().Run();

}

public static IWebHostBuilder CreateWebHostBuilder(string[] args) =>

WebHost.CreateDefaultBuilder(args)

.ConfigureLogging((hostingContext, logging) =>

{

logging.AddLog4Net();

})

.UseStartup<Startup>();

}

Logging can be done by injecting an ILogger in your code:

public class HomeController

{

private ILogger logger;

public HomeController(ILogger<HomeController logger)

{

this.logger = logger;

}

public IActionResult Index()

{

logger.LogInformation("Call to frontpage");

return View();

}

}

This blog post will be extended with the content you want to read about. Get in contact if you have ideas for log4net related subjects you would like us to add to the post

elmah.io: Error logging and Uptime Monitoring for your web apps

This blog post is brought to you by elmah.io. elmah.io is error logging, uptime monitoring, deployment tracking, and service heartbeats for your .NET and JavaScript applications. Stop relying on your users to notify you when something is wrong or dig through hundreds of megabytes of log files spread across servers. With elmah.io, we store all of your log messages, notify you through popular channels like email, Slack, and Microsoft Teams, and help you fix errors fast.

See how we can help you monitor your website for crashes Monitor your website